In 2012, former Oklahoma City Police Department polygraph operator-turned-critic Douglas Gene Williams published his autobiography under the title, From Cop to Crusader: My Fight Against the Dangerous Myth of “Lie Detection.” In 2014, he released a second edition, adding an account of the raid conducted by federal agents on his home and office as part of Operation Lie Busters, a federal investigation that targeted individuals providing instruction on how to pass or beat a polygraph “test.”

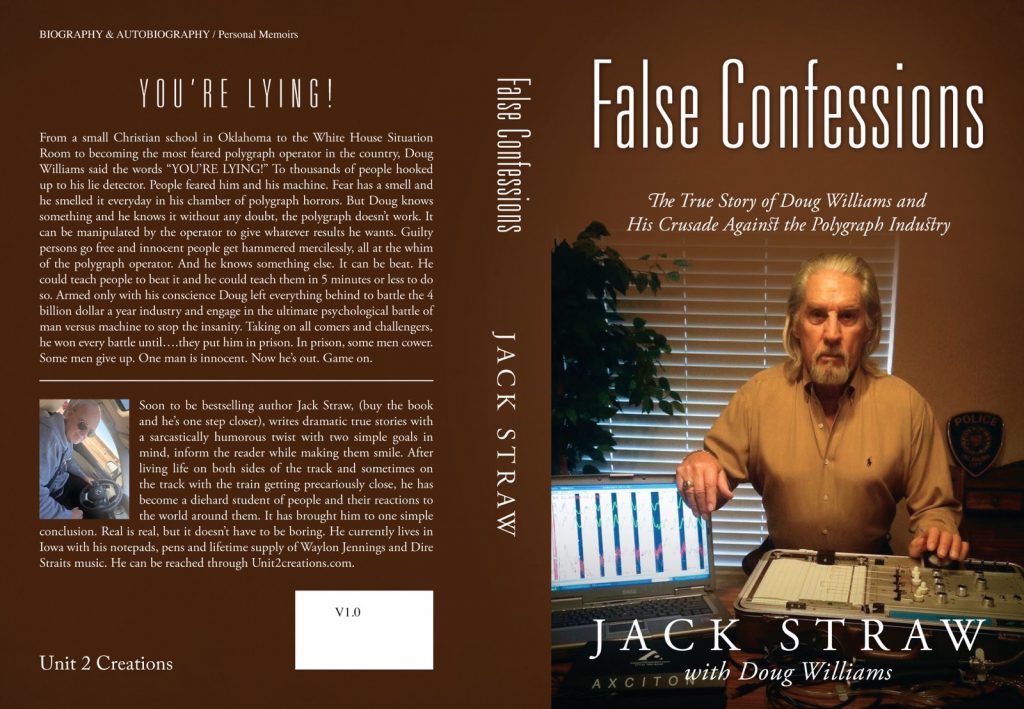

In 2015, Williams was sentenced to two years in prison for teaching undercover agents how to pass the polygraph. While incarcerated, he met Jack Straw, a fellow inmate and former Chicago police captain, with whom he has collaborated to retell his life story, now published under the title False Confessions: The True Story of Doug Williams and His Crusade Against the Polygraph (Unit 2 Creations: 2020).

Asked for comment about the choice of title (the book does not specifically go into any particular false confessions), Williams explained that he and Straw, in discussing problems with the polygraph in the criminal arena, both agreed that “it is the primary thing most responsible for all false confessions.”

In the introduction to From Cop to Crusader, Williams stated “This book is a recounting of actual events that have occurred during my crusade against the multi-billion dollar scam called ‘lie detection’ perpetrated by the polygraph industry. It is written to the best of my memory. But as someone once said, ‘Memory is a complicated thing, a relative to the truth, but not its twin.’ So, the characters, conversations, and entities depicted may be composites or fictitious.” This no doubt applies to False Confessions, as well, which reads very much like an oral history, with reconstructed conversations.

Straw’s retelling of Doug Williams’ story is without question better organized and told than the original. Divided into 34 chapters, it chronicles Williams’ time working as a U.S. Air Force enlisted man in the White House Communications Agency during the Johnson and Nixon administrations, his joining the Oklahoma City Police Department, and how he made the decision to apply for a polygraph position, which culminated in his attending the late Dick Arther’s National Training Center of Lie Detection in New York City.

Williams relates (in Chapter 4) one of the memorable incidents that led him to question what he was doing as a polygraph operator:

…A particularly haunting memory of a woman seated in my office, sobbing while I railed on her for a confession, returned to my mind almost daily. I had been pushing her for a confession.

“The polygraph says you’re lying!” I shouted…

“I didn’t do it,” she’d cried…

I screamed back, “The machine is not wrong. You are lying. The machine is never wrong!”

After hours of mental pummeling, she’d balled up into a near-fetal position, almost convulsing in anguish. Suddenly, this woman turned her face to look squarely at me and cried out, “I did not do it! What are you trying to do? My God, what is wrong with you?”

There it was. Very plain, and corrosive as acid. What WAS wrong with me? And, that question led to more questions, bigger questions. What was wrong with all of this lie-detection trickery and the massive cult of operators who held so much power? Where had it started? How had it grown? How had it lasted all this time? I knew I needed answers to these questions.

Williams goes on to describe his 1979 departure from the Oklahoma City Police Department, his objections to polygraphy, and his decision to go public with his concerns. In Chapter 7, Williams recalls a press event he held at an Oklahoma City hotel not long after his resignation. Among other notable things, Williams recalls:

I felt that it was important to give the crowd some foundation to my claims, so I explained my background and told them how I had come to learn about this abusive behavior. I explained that, aside from my job with the police department, I had also worked part-time for a private polygraph company, so I had firsthand knowledge of the abuses within the industry. I explained that the company I had worked for had actually encouraged us to fail as many people as possible in order to charge the employer more money for administering more polygraph exams. It was common practice among private polygraph examiners.

Williams also notes that not all companies that required polygraph screening at that time did so voluntarily:

…polygraph operators were a necessary evil for the owners and managers of businesses that required their employees to submit to this grueling ordeal. Many of the business owners resented having to give the test; however, they were required to do so by the insurance companies that covered their businesses against losses from theft by employees….

Williams goes on to recount the beginning of his crusade against polygraphy, starting with an appearance on a popular talk show on Oklahoma’s largest radio station, KTOK. He details his development of a “three-prong strategy” embracing education, legislation, and litigation. As part of the education prong, Williams wrote the original edition of his manual, “How to Sting the Polygraph,” which explains how to pass or beat a polygraph “test”:

To launch the Education Phase of my attack, I needed a textbook. So, I compiled information into a manual I called, How to Sting the Polygraph. It was a detailed, start-to-finish handbook on how to defend yourself from the polygraph and its operator. The techniques were simple, and a person could perform them with relative ease. But, I had one more thing to do in order to craft the manual into the ultimate textbook I wanted it to be. In order to round out my research so that the manual was completely authenticated, I decided to utilize all the techniques “undercover,” as you might say. I would take polygraph exams from different polygraphists, pass them, document them, and notify the operators that had given me the test of the said results.

In order to do this, I would have to relocate. Oklahoma City wouldn’t work. All the polygraph operators knew me, and they weren’t going to let me anywhere near their little rooms of deceit. So, after I left the P.D., I moved to Houston, Texas to launch my campaign….

Notably, the complete text of the latest edition of Williams’ “How to Sting the Polygraph” is included as an appendix to False Confessions.

While working in Houston as an apprentice machinist, Williams embarked on a letter-writing campaign, also giving radio interviews. He later returned to Oklahoma City where for a time he worked as a paralegal and attended (though did not ultimately complete) law school at Oklahoma City University.

As part of the litigation prong of his antipolygraph campaign, Williams convinced his employer, attorney and former Oklahoma City Police Officer Chris Eulberg, to represent a polygraph victim bringing a wrongful discharge suit against oil field services company Halliburton Services. While the case was ultimately not successful, depositions were held, and the case helped to bring attention to workplace polygraph abuse. Although Williams does not mention the name of the plaintiff, upon inquiry, he confirmed that it was Michael Crowley, whose plight was the subject of an 11 July 1983 article in The Oklahoman titled, “Test wipes out job.”

Another highlight is Williams’ account of his participation in the CBS 60 Minutes investigative report, “Truth and Consequences,” which aired on Sunday, 11 May 1986 (Chapters 21 and 22). In that report, three different polygraph operators chosen from the New York telephone directory accused three different individuals of theft, even though no theft had occurred.

Regarding the “legislative prong” of his campaign against the polygraph, Williams recounts (in Chapters 16 and 17) the story his 1985 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives, which helped lay the foundation for passage of the Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988.

The last four chapters are of special interest. They concern a federal investigation called Operation Lie Busters that targeted Williams for entrapment. Williams recounts the raid on his home and office conducted on 21 February 2013, his indictment more than a year later, his difficult decision to plead guilty two days into trial, his incarceration from 30 October 2015 until 26 July 2017, and his plans for the future.

A minor criticism is that book could have benefited from additional copy editing (for example, in decades, such as “the 1980s” there should be no apostrophe, and “more wizened” does not mean “made more wise.”) In addition, it is erroneously implied in Chapter 5 that William Moulton Marston introduced his blood pressure-based lie detector test in 1930, nearly a decade after John A. Larson had assembled the first polygraph instrument in 1921. Marston in fact had documented his idea for a lie detector as early as 1915, and Larson was inspired by Marston’s work. But again, these are minor points.

False Confessions is a must-read for students of the history of polygraphy. Doug Williams is indisputably among the most influential persons in polygraphy’s nearly century-long history. His revelation of the polygraph trade’s secrets has earned the wrath of polygraph operators across the United States, and his manual “How to Sting the Polygraph” has long been part of the curriculum for the federal polygraph school’s countermeasures course.

In addition, the targeting of Williams for entrapment by overzealous federal agents—who began their investigation in the absence of any evidence that he had committed any crime—has civil liberties implications that go well beyond the polygraph world.

On a final note, polygraph operators (and those contemplating attending polygraph school) are well-advised to reflect on Williams’ saga and to think long and hard about the ethical implications of practicing this fraudulent pseudoscience.

False Confessions is available directly from the publisher. At the time of writing, discounted copies are also available via Outskirts Press, as is an Amazon Kindle version (presently free with Kindle Unlimited).

Update 19 June 2020: AntiPolygraph.org readers may obtain copies of False Confessions signed by Jack Straw and Doug Williams at a $3 discount by using code E29J9EE when ordering directly from Unit 2 Creations.

What a brave man!