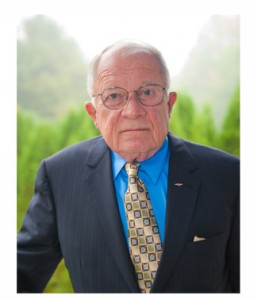

Disbarred criminal defense lawyer F. Lee Bailey will be the keynote speaker at a seminar jointly presented by the American Polygraph Association and the Maine Polygraph Association next Wednesday to Friday, 24-26 April 2013 in Saco, Maine. The stated purpose of the seminar is “to educate lawyers, investigators, therapists, probation and governmental officers and members of the judiciary on the current state of polygraph – often referred to by the misnomer ‘Lie Detector’ – usage in the United States.” Such individuals will be required to pay $250 for the privilege. It is perhaps fitting that a crooked lawyer would be selected as keynote speaker by practitioners of a crooked profession: polygraphy depends on the operator lying to and otherwise deceiving the person being “tested,” and the American Polygraph Association doesn’t think it’s an ethical problem that one of their past presidents, Ed Gelb, falsely passed himself off as a Ph.D. in marketing his polygraph services. Incidentally, Gelb and Bailey collaborated in a television show called “Lie Detector” (which Bailey avers is a misnomer) that aired from 1982-83.

Bailey, a life member of the American Polygraph Association, was disbarred by the Supreme Court of Florida on 21 November 2001 for “multiple counts of egregious misconduct, including offering false testimony, engaging in ex parte communications, violating a client’s confidences, violating two federal court orders, and trust account violations, including commingling and misappropriation.” On 30 November 2012, the Maine Board of Bar Examiners rejected Bailey’s application for admission.

A report by Seth Koenig of the Bangor Daily News indicates that the purpose of this conference is not merely to “educate” individuals about the current usage of polygraphy in the United States but to advocate its expansion:

In Portland on Wednesday, Bailey said the polygraph test — often called a “lie detector test,” although he said the term is inaccurate — is “woefully” underutilized in Maine.

“This very simple, and not very expensive, technique can save Maine law enforcement officials a lot of grief,” Bailey told reporters. “The police spend a lot of time interviewing liars and chasing false suspects.”

During criminal investigations, polygraph testing can be used often, not necessarily to pinpoint the guilty party, but to rule out suspects and clear clutter in the case, he said. Bailey said that while individuals who “show deception” on a polygraph test cannot be determined definitively to be lying — partial truths, among other responses, could set off the device without being outright false, he said — the test “can help prove when somebody is telling the truth.”

“If you get a [‘no deception indicated’ response], you should be off the list [of suspects for a crime],” he said. “If you don’t, we would just ask you some more questions.”

The notion that a suspected criminal who passes a polygraph can be cleared is a dangerous delusion. Polygraphy has no scientific basis and any reliance upon it is liable to misdirect investigations, as happened in the case of Green River Killer Gary Leon Ridgway, who passed a polygraph “test” and killed again…and again. Moreover, polygraphy is vulnerable to simple, effective countermeasures that polygraph operators cannot detect. These are documented in Chapter 4 of AntiPolygraph.org’s free book, The Lie Behind the Lie Detector (1 mb PDF).

Bailey also advocates releasing half of Maine’s prison population and placing them under “polygraph supervision”:

Bailey also said extensive and regular polygraph usage in Maine would cut down dramatically on the recidivism in Maine prisons.

“We’ve got a lot of people in the state of Maine’s prisons who don’t need to be there,” he said. “We can control them without supporting them [financially]. … There’s no earthly reason why this type of polygraph supervision would not work in Maine.”

Bailey said the threat of regular polygraph tests has been shown to reduce repeat offenses. In states where the tests are used to regularly interview sex offenders after release, he said, repeat offense rates dropped from as high as 70 percent to as low as 19 percent.

According to seminar coordinator Mark Teceno, the Maine Legislature in 2004 passed a law requiring polygraph testing to be part of the post-release treatment for sex offenders in the state. But Teceno said the testing is still not frequent or regular enough, and he added the measure should be expanded for use with individuals convicted of other crimes, as well.

Bailey said he believes those steps would cut Maine’s general inmate population from about 2,000 people to about 1,000 — with the difference from inmates released early under “polygraph supervision” and those who are deterred from committing repeat offenses because of the testing.

“If I’m right, I’d be willing to go on every single one of your stations and say, ‘Nyah, nyah, na-nyah, nyah,’” he said. “If I have to eat crow, well, I’ve got a strong stomach.”

Again, owing to polygraphy’s lack of scientific underpinnings and vulnerability to easily-learned countermeasures, Bailey’s proposal would undermine public safety. To our knowledge, Bailey’s claim that post-conviction sex offender polygraph programs have reduced recidivism rates from 70 to 19 percent is unfounded. With respect to post-conviction polygraph screening, see criminology professor Jeffrey W. Rosky’s talk, “Examining Post-Conviction Polygraph Testing”:

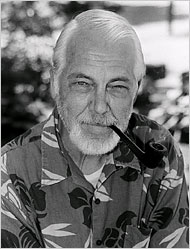

One might also surmise that Bailey will advocate, as he has in the past, admission of polygraph “evidence” in criminal trials. The late David T. Lykken addressed this question in his seminal work on polygraphy, A Tremor in the Blood: Uses and Abuses of the Lie Detector ((2nd ed. 1998. Plenum Trade, at p. 258.)):

Suppose instead that the courts accede to F. Lee Bailey’s proposal and permit the defense to offer lie test evidence over the objection of the prosecution. The humane intention here would be to compensate for the greater resources available to the state by giving the defendant this opportunity to prove his innocence. We must now imagine every defendant shopping for a friendly polygrapher in the hope of achieving a “pass” that could be offered into evidence–and that no defendants would offer testimony of a failed test. That is, we are now talking about criminal defendants against whom the evidence is strong enough for the prosecution to bring them to trial, rather than the subgroup against whom the prosecution’s evidence is weak. If we assume that 80 out of each 100 criminal defendants brought to trial are in fact guilty (most officers of the court would probably set the figure higher), then about 12 of the guilties and 12 of the innocents should present evidence of passed lie tests, evidence that will be wrong 50% of the time. ((Based on field studies, Lykken is assuming here that 85% of guilty and 40% of innocent suspects will fail the polygraph.)) This unhappy result is based on the assumption that lie tests given privately to Mr. Bailey’s clients are as accurate in detecting lying as those given under adversarial conditions. We shall see in the next section that these “friendly” polygraph tests are in fact more likely to be passed by guilty defendants. This chance level of errors also assumes that none of the guilty defendants who can afford defense attorneys in Mr. Bailey’s class will have learned–in Chapter 19 of this book or in diverse other ways–how to beat the lie detector even though guilty. Because both assumptions are so dubious, it is likely that admission of exculpatory polygraph test results into evidence at trial will have a probative value that is negative.

Rather than pay $250 to be educated by the likes of F. Lee Bailey, lawyers, investigators, therapists, probation and governmental officers and members of the judiciary would be better off picking up a copy of Lykken’s A Tremor in the Blood. It’s available on Amazon.com or at any good research library.