On 4 April 2013, the Center for Investigative Reporting published two articles by Andrew Becker on U.S. Customs and Border Patrol’s pre-employment polygraph screening program. The first, which has garnered considerable attention and was featured on Tina Brown’s The Daily Beast, is “During polygraphs, border agency applicants admit to rape, kidnapping.” ((The Daily Beast ran with the less sensationalist title, “On Polygraph Tests, Would Be Border Patrol Agents Confess to Crimes”)) Becker’s reporting is based primarily on an internal report by CBP’s polygraph unit (formally titled the Credibility Assessment Division). This document, first obtained by the Center for Investigative Reporting, is available on AntiPolygraph.org as a word-searchable PDF file. Becker opens the article:

One [CBP applicant] admitted to kidnapping and ransoming hostages in the Ivory Coast. Others said they had molested children or committed rape. And one, as he prepared for survival in a post-apocalyptic world, contemplated assassinating President Barack Obama.

These are among the thousands of applicants who have sought sensitive law enforcement jobs in recent years with the U.S. Border Patrol and its parent agency, Customs and Border Protection.

In many cases, these people made it all the way through the hiring process until one of the last steps – a polygraph exam. Once sitting with a polygraph examiner, they admitted to a host of astonishing crimes, according to documents obtained by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

The records – official summaries of more than 200 polygraph admissions – raise alarms about the thousands of employees Customs and Border Protection has hired over the past six years before it began mandatory polygraph tests for all applicants six months ago. The required polygraphs come at the tail end of a massive hiring surge that began in 2006 and eventually added 17,000 employees, helping to make the agency the largest law enforcement operation in the country.

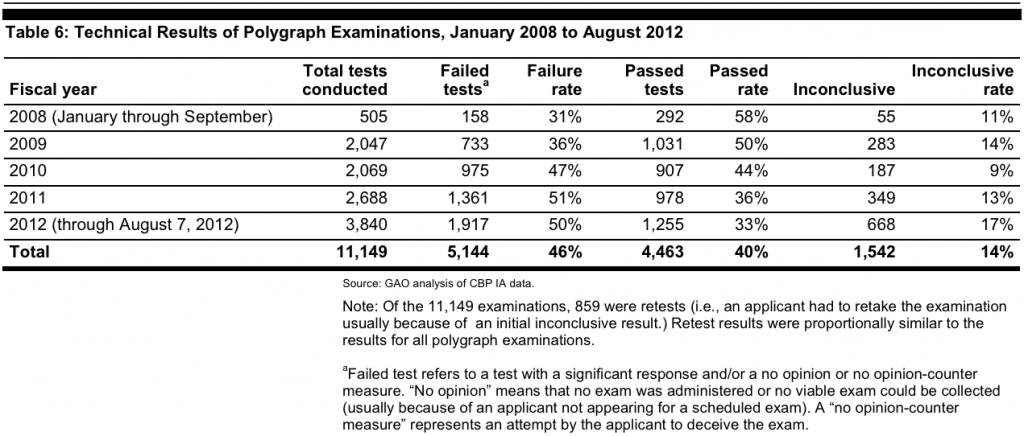

Indeed, some of these applicants did admit to serious criminal behavior. Based on public reaction on Twitter, it would seem that many infer that that such conduct is commonplace among CBP applicants. But do the numbers justify such alarm? The CBP signficant admissions summary (5.4 mb PDF) adduces some 220 admissions from 2008 to 2012. (There are 221 items in the list, but the first is not an admission.) A report by the Government Accountability Office documents that during this period, CBP conducted some 11,149 polygraph examinations:

Thus, the 220 substantive admissions account for just under 2% of the polygraph examinations conducted.

Becker enumerates some of the reported admissions:

The 200-plus “significant admissions” described in the summary reports paint a small yet troubling portrait of some of the kinds of people who have applied to be Border Patrol agents and customs officers since 2008. They also highlight potential weaknesses in the costly hiring process that failed to screen out questionable applicants earlier.

In one case from February, Jose Ramirez, 25, admitted during a polygraph exam that he was the driver in a 2009 single-car crash that killed someone. He previously told investigators in Yuma, Ariz., that the dead passenger was the driver, according to the Yuma County Sheriff’s Office. Ramirez now faces second-degree murder and other charges.

One applicant admitted to smoking marijuana 20,000 times in a 10-year-period. Another was more bizarre: “Applicant had no independent recollection of the events that resulted in a blood doused kitchen and was uncertain if he committed any crime during his three hour black out,” according to the Customs and Border Protection summary.

In another example, a woman seeking a job with the bureau told an examiner that she smuggled marijuana into the country – typically by taping 10 pounds of the drug to her body – about 800 times. Scores more admitted that they had engaged in or had relatives involved in human smuggling or drug running. Some said they harbored immigrants not authorized to be in the U.S. or had family members living in the country illegally.

These admissions are indeed disturbing, but they should not be mistaken for evidence of the validity of polygraphy. There is broad consensus in the scientific community that polygraphy is without scientific basis. It is only useful for getting admissions to the extent that the person being “tested” doesn’t understand that the “test” is a sham.

Becker also writes:

The summaries disclose dozens of attempts to infiltrate the agency, including 10 applicants believed to have links to organized crime who had received sophisticated training on how to defeat the polygraph exam, according to Customs and Border Protection.

This is a reference to the first paragraph of the CBP admissions report. But a review of the actual report reveals that no admission is alleged with respect to any of these 10 applicants, and the CBP report does not allege that they were believed to have links to organized crime, though it does speak of a “conspiracy.” For commentary on this alleged infiltration attempt, see “U.S. Customs and Border Protection Reveals Criminal Investigation Into Polygraph Countermeasure Training” on this blog and “Is It a Crime to Provide or Receive Polygraph Countermeasure Training?” on the AntiPolygraph.org message board.

The CBP polygraph admission summary goes on to enumerate 17 additional alleged “infiltration attempts” (paras. 2-18). However, a close reading of these paragraphs reveals that only one (para. 15) clearly involves an applicant allegedly seeking CBP employment for nefarious reasons, and in that one instance, there was no admission. Polygraph examiners are typically rated on the basis of admissions obtained after a failed polygraph examination. This provides a perverse incentive to exaggerate the significance of admissions obtained. Polygraph units also have an incentive to overstate admissions in order to justify their budgets (and indeed, their very existence). Such incentives may help to explain the CBP polygraph unit’s dubious claims of having detected “infiltration attempts.” In any event, it would be a very stupid infiltrator indeed who would confess during a polygraph examination. It is likely that the great majority of any infiltrators would make no admissions against their self-interest.

Becker also addresses a CBP internal study called the “Clear Shelf Initiative” (123 kb PDF) in which 283 applicants who were otherwise cleared for hire completed polygraph examinations. 44% failed the polygraph, and 38% of these made “unsuitable” (disqualifying) admissions. 44% passed, but even among these, 10% made disqualifying admissions. Under polygraph protocols, only those who fail are subjected to a post-test interrogation, which is the point at which most admissions are obtained. One can only wonder what disqualifying admission rate might have been obtained had all those who passed also been subjected to a post-test interrogation.

Regarding a second CBP internal study (1.1 mb PDF), Becker writes:

Another internal study, “Test versus No Test,” found in 2010 that employees who had not taken the polygraph exam were more than twice as likely to engage in misconduct, such as stealing government property or drug abuse, than those who took the screening before they were hired.

This study (actually, a 2-page summary) may raise more questions than it answers. It states that 1,293 CBP applicants passed pre-employment polygraph examinations between fiscal years 2008 and 2010. But only 203 (15.7%) of these went on to enter duty and attend the training academy. What happened to the remaining 84.3% who passed the polygraph? The study does not address why they did not enter duty.

The 203 who passed the polygraph and entered duty were compared with a randomly selected group of 203 recruits hired during the same period who were not polygraphed. During the study period (three years) 20 of those polygraphed were determined to be “of record” with Internal Affairs while 41 of those not polygraphed were “of record.” This indeed would suggest that polygraphed recruits are less likely to get into trouble than those not polygraphed (though without additional documentation of the study, it is not possible to adequately assess its methodological soundness). In any event, it should be a matter of concern that even among those polygraphed, some 10% were “of record” with Internal Affairs within three years being hired.

Becker also notes:

Internal affairs officials have considered requiring polygraphs for current employees. But such a move, which would have to be approved by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, could face stiff resistance from unions that represent the bureau’s frontline employees and some high-ranking officials alike.

“If you were to survey the agents, you’d probably find out a good percentage failed a polygraph elsewhere and they’re doing a good job here,” said Chris Bauder, executive vice president of the National Border Patrol Council, the agents union. “Lots of corruption cases could have been caught if they had gone through a thorough background investigation.”

If polygraphy were truly a valid means of detecting deception, wouldn’t it make sense to polygraph current employees on an ongoing (preferably random) basis, even more so than applicants? After all, most new recruits haven’t yet had the opportunity to become corrupt. Yet the National Border Patrol Council has good reason to be leery of the polygraph.

In a second article that received considerably less attention, Becker notes that even though Congress (in 1988) prohibited most use of polygraphs in private sector employment owing to concerns over its reliability, the federal government has since then only increased its use of polygraphs. Becker recounts the story of one victim of the CBP pre-employment polygraph screening program:

Eric Trevino, however, is not willing to accept that Customs and Border Protection considers him dishonest. Trevino, 37, of Harlingen, Texas, is one of three applicants who told the Center for Investigative Reporting that they had wrongly failed the polygraph.

Seeking a job as a customs officer, Trevino failed the polygraph exam in June 2010 and was barred from retaking the exam for three years. He hopes to take the exam again this summer as a Border Patrol applicant, which has a higher age limit for new employees.

Born and raised in the Rio Grande Valley, Trevino grew up traveling into Mexico to eat and go shopping with his family. He said his dream job is to be a customs officer. He said he has an uncle who is an agent with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and Customs and Border Protection recently hired his brother.

When asked if he had ties to foreign nationals or drug traffickers and whether he ever went to terrorist training, Trevino answered no. But the examiner said he was less than truthful and had erratic breathing, a possible countermeasure to defeat the test, according to Trevino.

“It seemed more like an interrogation. I’ve never been arrested. I’ve got two speeding tickets in my life. I don’t smoke or drink,” Trevino said. “The frustration is when I know I’m not lying about it, but the machine says I am, especially terrorist training and loyalties to America. It’s like, give me a break.”

Given polygraphy’s lack of scientific underpinnings, it is clear that many of the roughly 60% of CBP applicants who fail to pass the polygraph are being falsely accused of deception and wrongly denied employment for which they are qualified. AntiPolygraph.org believes this practice is immoral and runs counter to basic human values of fairness. Polygraphy’s utility depends on perpetuation of a false public belief that it is a scientifically sound test for deception. It is no such thing. As we have documented in The Lie Behind the Lie Detector (1 mb PDF), polygraph “testing” is a pseudoscientific fraud that actually depends on the polygraph operator lying to and deceiving the person being “tested.” The procedure is inherently biased against the most truthful and conscientious of persons, and yet susceptible to simple countermeasures that polygraph operators have no demonstrated ability to detect.

In its landmark report, The Polygraph and Lie Detection (10.3 mb PDF), the National Research Council warned that “polygraph testing yields an unacceptable choice…for employee security screening between too many loyal employees falsely judged deceptive and too many major security threats left undetected. Its accuracy in distinguishing actual or potential security violators from innocent test takers is insufficient to justify reliance on its use in employee security screening in federal agencies” and that “overconfidence in the polygraph–a belief in its accuracy not justified by the evidence–presents a danger to national security objectives.”

It’s high time the U.S. government started heeding the science on polygraphs.